A Double Pendulum Example¶

Problem Description¶

The double pendulum is a classic example of a chaotic system. It is a well documented and understood example. Read [here](wp>Double_pendulum) for more details.

This example has 2 particles of the same mass, on massless links of the same length.

Deriving the equations of motion with SymPy¶

from sympy import symbols

from sympy.physics.mechanics import *

q1, q2 = dynamicsymbols('q1 q2')

q1d, q2d = dynamicsymbols('q1 q2', 1)

u1, u2 = dynamicsymbols('u1 u2')

u1d, u2d = dynamicsymbols('u1 u2', 1)

l, m, g = symbols('l m g')

N = ReferenceFrame('N')

A = N.orientnew('A', 'Axis', [q1, N.z])

B = N.orientnew('B', 'Axis', [q2, N.z])

A.set_ang_vel(N, u1 * N.z)

B.set_ang_vel(N, u2 * N.z)

O = Point('O')

P = O.locatenew('P', l * A.x)

R = P.locatenew('R', l * B.x)

O.set_vel(N, 0)

P.v2pt_theory(O, N, A)

R.v2pt_theory(P, N, B)

ParP = Particle('ParP', P, m)

ParR = Particle('ParR', R, m)

kd = [q1d - u1, q2d - u2]

FL = [(P, m * g * N.x), (R, m * g * N.x)]

BL = [ParP, ParR]

KM = KanesMethod(N, q_ind=[q1, q2], u_ind=[u1, u2], kd_eqs=kd)

(fr, frstar) = KM.kanes_equations(FL, BL)

kdd = KM.kindiffdict()

mm = KM.mass_matrix_full

fo = KM.forcing_full

qudots = mm.inv() * fo

qudots = qudots.subs(kdd)

qudots.simplify()

mechanics_printing()

mprint(qudots)

Running the above code will give the following python code output in the console (order is \(\dot{q}_1\), \(\dot{q}_2\), \(\dot{u}_1\), \(\dot{u}_2\)):

[u1]

[u2]

[(-g*sin(q1)*sin(q2)**2 + 2*g*sin(q1) - g*sin(q2)*cos(q1)*cos(q2) + 2*l*u1**2*sin(q1)*cos(q1)*cos(q2)**2 - l*u1**2*sin(q1)*cos(q1) - 2*l*u1**2*sin(q2)*cos(q1)**2*cos(q2) + l*u1**2*sin(q2)*cos(q2) + l*u2**2*sin(q1)*cos(q2) - l*u2**2*sin(q2)*cos(q1))/(l*(sin(q1)**2*sin(q2)**2 + 2*sin(q1)*sin(q2)*cos(q1)*cos(q2) + cos(q1)**2*cos(q2)**2 - 2))]

[(-sin(q1)*sin(q2)/2 - cos(q1)*cos(q2)/2)*(2*g*l*m*sin(q1) - l**2*m*(-sin(q1)*cos(q2) + sin(q2)*cos(q1))*u2**2)/(l**2*m*(sin(q1)*sin(q2)/2 + cos(q1)*cos(q2)/2)*(sin(q1)*sin(q2) + cos(q1)*cos(q2)) - l**2*m) + (g*l*m*sin(q2) - l**2*m*(sin(q1)*cos(q2) - sin(q2)*cos(q1))*u1**2)/(l**2*m*(sin(q1)*sin(q2)/2 + cos(q1)*cos(q2)/2)*(sin(q1)*sin(q2) + cos(q1)*cos(q2)) - l**2*m)]

These equations are the four first order differential equations that completely described the systems motion at any time.

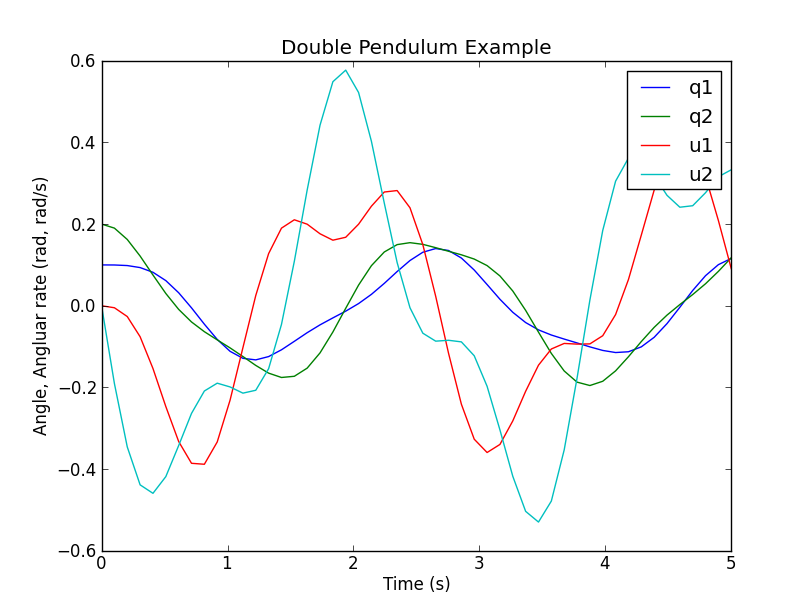

Integration with Scipy¶

These equations can also be computed with the SciPy libraries.

You can use the experimental code output function. This shows how the code output would work for the double pendulum example. You can either put this at the end of your script, or run it while in the interpreter.

You can supply a file name for the settings file, otherwise a default will be provided. If an alternative settings file name is given, that will be the default file name in the integration file. Note that once the settings file has been written once, it does not need to be written again. Additionally, multiple settings files can be written; the most recent one will be the default settings file in the integration file.

You can either run the file from the interpreter, as “run outfile.py”, from the command line as “python outfile.py”, or from the command line specifying a settings file as “python outfile.py settings_file.csv”.

# append the following code to your script, or run it in the interpreter after you run your script

co = code_output(KM, "outfile")

co.get_parameters()

# output should be [m, g, l]

co.give_parameters([1, 9.81, 1])

co.get_initialconditions()

# output should be [q1, q2, u1, u2]

co.give_initialconditions([.1, .2, 0, 0])

co.give_time_int([0,10,1000])

co.write_settings_file()

co.write_rhs_file('SciPy')

run outfile.py

Integration with Matlab¶

A integration routine can be written in Matlab in a similar fashion as Scipy. The syntax just varies slightly. The complete m-file can be downloaded from [double_pendulum.m](https///github.com/gilbertgede/pydy_examples/blob/master/double_pendulum/double_pendulum.m).

The first step is to write the a function that returns the derivatives of the states as a function of time and the current state:

function xd = state_derivatives(t, x, m, l, g)

%function xd = state_derivatives(t, x, m, l, g)

% Returns the derivatives of the states as a function of the current state

% and time.

%

% Parameters

% ----------

% t : double

% Current time.

% x : vector, (4, 1)

% Current state.

% m : double

% The mass of each particle.

% l : double

% Length of each link.

% g : double

% Acceleratoin due to gravity.

%

% Returns

% -------

% xd : matrix, 4 x 1

% The derivatives of the states in this order [q1, q2, u1, u2].

% Unpack the variables so that you can use the sympy equations as is.

q1 = x(1);

q2 = x(2);

u1 = x(3);

u2 = x(4);

% Initialize a vector for the derivatives.

xd = zeros(4, 1);

% Calculate the derivatives of the states. These equations can be copied

% directly from the sympy output but be sure to print with `mprint` in

% sympy.physics.mechanics to remove the `(t)` and use Matlab's find and

% replace and regular expressions to change the python `**` to the matlab

% `^`.

xd(1) = u1;

xd(2) = u2;

xd(3) = (-g * sin(q1) * sin(q2)^2 + 2 * g * sin(q1) - g * sin(q2) * ...

cos(q1) * cos(q2) + 2 * l * u1^2 * sin(q1) * cos(q1) * ...

cos(q2)^2 - l * u1^2 * sin(q1) * cos(q1) - 2 * l * u1^2 * ...

sin(q2) * cos(q1)^2 * cos(q2) + l * u1^2 * sin(q2) * cos(q2) + ...

l * u2^2 * sin(q1) * cos(q2) - l * u2^2 * sin(q2) * cos(q1)) / ...

(l * (sin(q1)^2 * sin(q2)^2 + 2 * sin(q1) * sin(q2) * cos(q1) * ...

cos(q2) + cos(q1)^2 * cos(q2)^2 - 2));

xd(4) = (-sin(q1) * sin(q2) / 2 - cos(q1) * cos(q2) / 2) * (2 * g * ...

l * m * sin(q1) - l^2 * m * (-sin(q1) * cos(q2) + sin(q2) * ...

cos(q1)) * u2^2) / (l^2 * m * (sin(q1) * sin(q2) / 2 + cos(q1) * ...

cos(q2) / 2) * (sin(q1) * sin(q2) + cos(q1) * cos(q2)) - l^2 * m) + ...

(g * l * m * sin(q2) - l^2 * m * (sin(q1) * cos(q2) - sin(q2) * ...

cos(q1)) * u1^2) / (l^2 * m * (sin(q1) * sin(q2) / 2 + cos(q1) * ...

cos(q2) / 2) * (sin(q1) * sin(q2) + cos(q1) * cos(q2)) - l^2 * m);

The equations of motion, xd, can be directly copied from the sympy.mechanics.physics output above, except that you must change the power operator, ‘**’, from python to the power operator used in Matlab, ‘^’.

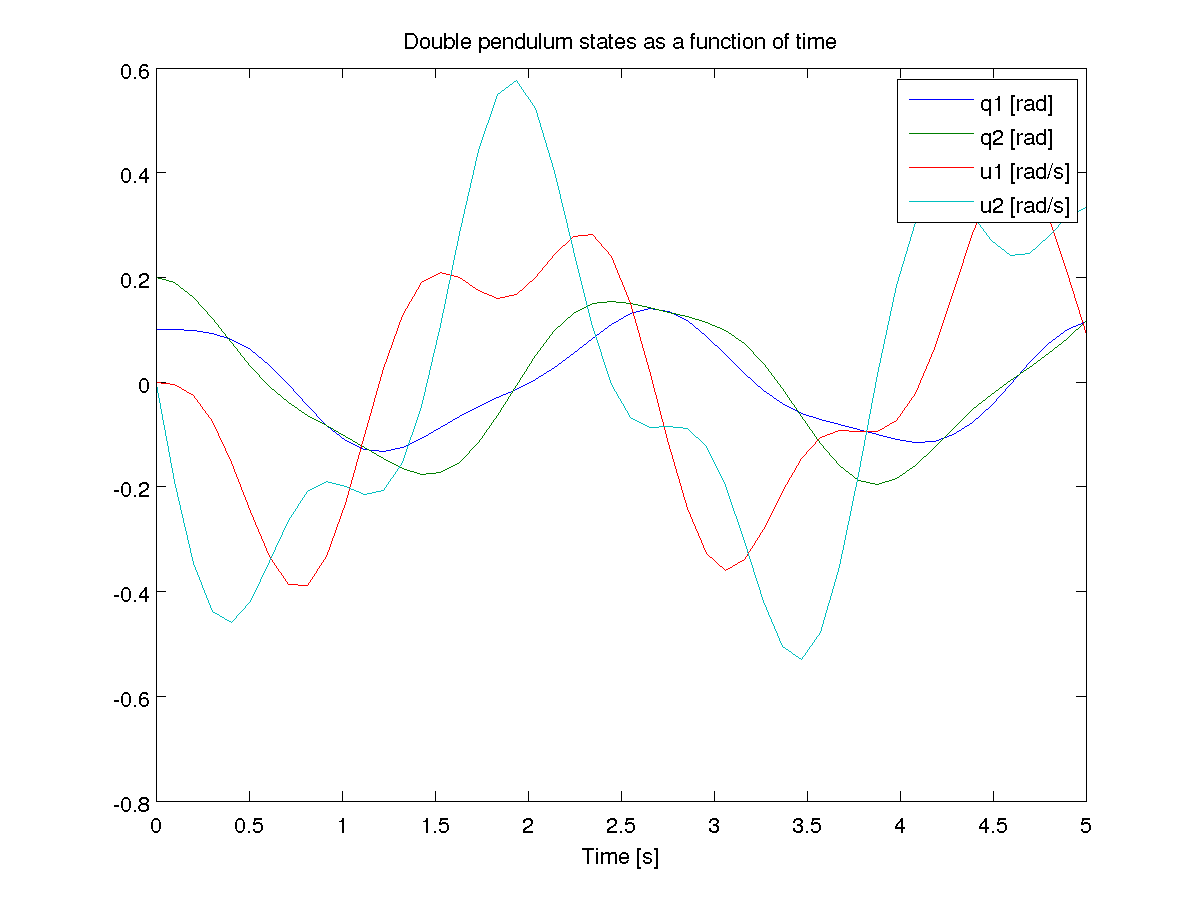

You now can use one of Matlab’s built-in ode integration routines, such as ode45, to integrate the equations of motion and get the time histories of the states.

% Integrate the equations over from 0 to 5 seconds with 50 steps.

timeSpan = linspace(0.0, 5.0, 50);

% Set initial angles in radians and the initial speeds to zero.

initialConditions = [0.1, 0.2, 0.0, 0.0];

% Define particles' mass, pendulums' length, and the acceleration due to

% gravity.

m = 1.0;

l = 1.0;

g = 9.8;

% Create a function handle to an anonymous function which which can pass the

% parameters.

f = @(t, x) state_derivatives(t, x, m, l, g);

% Integrate the equations of motion with default integration settings.

[t, x] = ode45(f, timeSpan, initialConditions);

The states as a function of time are now available. Use Matlab’s plotting functions to visualize the motion.

% Plot the results.

fig = figure();

plot(t, x)

title('Double pendulum states as a function of time')

xlabel('Time [s]')

legend('q1 [rad]', 'q2 [rad]', 'u1 [rad/s]', 'u2 [rad/s]')

Simulating with C/C++, GSL, plotting with matplotlib¶

Sometimes it is useful, for performance reasons, to write the main numerical part of your code in a compiled language like C, C++, or Fortran. This example illustrates how to do the main part of the simulation in C++, but then do the plotting with matplotlib.

double_pendulum.h

#ifndef DOUBLE_PENDULUM_H

#define DOUBLE_PENDULUM_H

double double_pendulum_ke(const double x[4], const double params[3]);

double double_pendulum_pe(const double x[4], const double params[3]);

int double_pendulum_ode(double t, const double x[], double dxdt[], void *_params);

#endif

The SymPy function ccode() is a very handy way to take a sympy expression and convert it to a C statement that will compile. Using this function, we can form the ODE function, as well as kinetic and potential energy functions for the double pendulum. All of the functions in the following file were obtained by a simple copy/paste of the output of the ccode() function in Sympy.

double_pendulum.cc

#include "double_pendulum.h"

#include `<cmath>`

#include `<gsl/gsl_errno.h>`

#include `<gsl/gsl_odeiv2.h>`

double double_pendulum_ke(const double x[4], const double params[3])

{

double m = params[0], l = params[2];

return 1.0*pow(l, 2)*(sin(x[0])*sin(x[1]) + cos(x[0])*cos(x[1]))*x[2]*x[3]/m + 1.0*pow(l, 2)*pow(x[2], 2)/m + 0.5*pow(l, 2)*pow(x[3], 2)/m;

}

double double_pendulum_pe(const double x[4], const double params[3])

{

double m = params[0], g = params[1], l = params[2];

return -g*m*(2*l*cos(x[0]) + l*cos(x[1]) - 3*l);

}

int double_pendulum_ode(double t, const double x[], double dxdt[], void *_params)

{

double const *params = static_cast`<double const *>`(_params);

double m = params[0], g = params[1], l = params[2];

dxdt[0] = x[2];

dxdt[1] = x[3];

dxdt[2] = (-g*sin(x[0])*pow(sin(x[1]), 2) + 2*g*sin(x[0]) - g*sin(x[1])*cos(x[0])*cos(x[1]) + 2*l*pow(x[2], 2)*sin(x[0])*cos(x[0])*pow(cos(x[1]), 2) - l*pow(x[2], 2)*sin(x[0])*cos(x[0]) - 2*l*pow(x[2], 2)*sin(x[1])*pow(cos(x[0]), 2)*cos(x[1]) + l*pow(x[2], 2)*sin(x[1])*cos(x[1]) + l*pow(x[3], 2)*sin(x[0])*cos(x[1]) - l*pow(x[3], 2)*sin(x[1])*cos(x[0]))/(l*(pow(sin(x[0]), 2)*pow(sin(x[1]), 2) + 2*sin(x[0])*sin(x[1])*cos(x[0])*cos(x[1]) + pow(cos(x[0]), 2)*pow(cos(x[1]), 2) - 2)) ;

dxdt[3] = (-sin(x[0])*sin(x[1])/2 - cos(x[0])*cos(x[1])/2)*(2*g*l*m*sin(x[0]) - pow(l, 2)*m*(-sin(x[0])*cos(x[1]) + sin(x[1])*cos(x[0]))*pow(x[3], 2))/(pow(l, 2)*m*(sin(x[0])*sin(x[1])/2 + cos(x[0])*cos(x[1])/2)*(sin(x[0])*sin(x[1]) + cos(x[0])*cos(x[1])) - pow(l, 2)*m) + (g*l*m*sin(x[1]) - pow(l, 2)*m*(sin(x[0])*cos(x[1]) - sin(x[1])*cos(x[0]))*pow(x[2], 2))/(pow(l, 2)*m*(sin(x[0])*sin(x[1])/2 + cos(x[0])*cos(x[1])/2)*(sin(x[0])*sin(x[1]) + cos(x[0])*cos(x[1])) - pow(l, 2)*m);

return GSL_SUCCESS;

}

To numerically integrate the equations, and save the time history of the states and energies to a data file, our main driver is as follows:

#include `<fstream>`

#include `<gsl/gsl_odeiv2.h>`

#include "double_pendulum.h"

struct simdata { double t, x[4], pe, ke; }; // t, q1, q2, u1, u2, pe, ke

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

double params[] = {1.0, 9.81, 1.0}; // m, g, l

simdata s = {0.0, {0.1, 0.2, 0.0, 0.0}}; // initial time and state

s.ke = double_pendulum_ke(s.x, params); // initial kinetic energy

s.pe = double_pendulum_pe(s.x, params); // intial potential energy

const double tf = 5.0; // final time

const int N = 501; // number of points

// GSL setup code

gsl_odeiv2_system sys = {double_pendulum_ode, NULL, 4, params};

gsl_odeiv2_driver * d = gsl_odeiv2_driver_alloc_y_new(&sys, gsl_odeiv2_step_rk8pd, 1e-6, 1e-6, 0.0);

// Open a file for writing

std::ofstream f("datafile.dat", std::ios::binary | std::ios::out);

// Simulation loop

f.write((char *) &s, sizeof(simdata)); // Write initial time data

for (int i = 1; i <= N; ++i) {

double ti = i * tf / N;

gsl_odeiv2_driver_apply(d, &(s.t), ti, s.x); // integrate the ODE's

s.ke = double_pendulum_ke(s.x, params); // compute kinetic energy

s.pe = double_pendulum_pe(s.x, params); // compute potential energy

f.write((char *) &s, sizeof(simdata)); // write to file

}

gsl_odeiv2_driver_free(d); // free resources

f.close(); // close file

return 0;

}

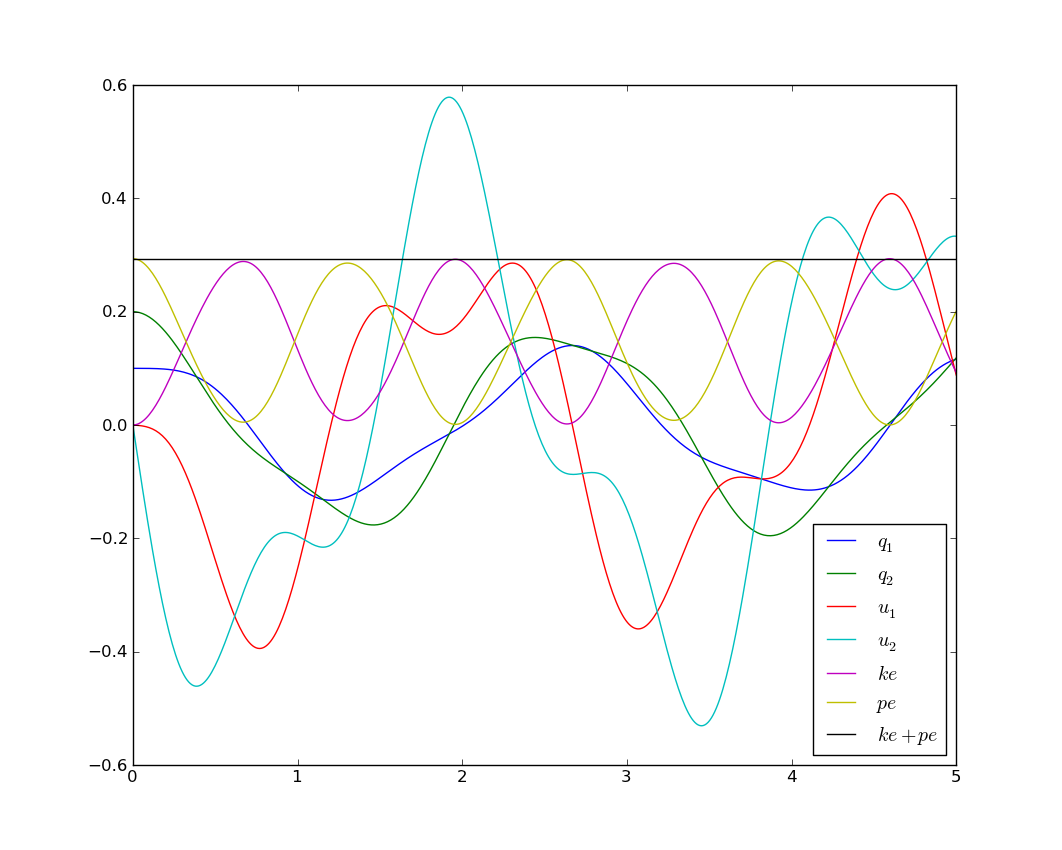

When you run this, a binary data file will be created in your current working directory. You can plot the data with the following Python code that makes use of Matplotlib:

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import os

# Define a data type for the simdata structure

simdata = np.dtype([('t', np.float64),

('q1', np.float64),

('q2', np.float64),

('u1', np.float64),

('u2', np.float64),

('pe', np.float64),

('ke', np.float64)])

os.system('./double_pendulum_sim') # run the simulation

data = np.fromfile('datafile.dat', dtype=simdata) # read the data

plt.plot(data['t'], data['q1'], label='$q_1$')

plt.plot(data['t'], data['q2'], label='$q_2$')

plt.plot(data['t'], data['u1'], label='$u_1$')

plt.plot(data['t'], data['u2'], label='$u_2$')

plt.plot(data['t'], data['ke'], label='$ke$')

plt.plot(data['t'], data['pe'], label='$pe$')

plt.plot(data['t'], data['pe'] + data['ke'], label='$ke+pe$')

plt.legend(loc=0)

plt.show()

Which results in the following nice plot:

Animation with Matplotlib¶

Matplotlib 1.1 has an animation module that makes 2D animation easy. Check out this tutorial for animating a double pendulum:

Resources¶

All of the source code for the examples can be found in https://github.com/gilbertgede/pydy_examples.